- Home

- News and events

- Find news

- Researchers document thousand-year-old graffiti in Kyiv

Researchers document thousand-year-old graffiti in Kyiv

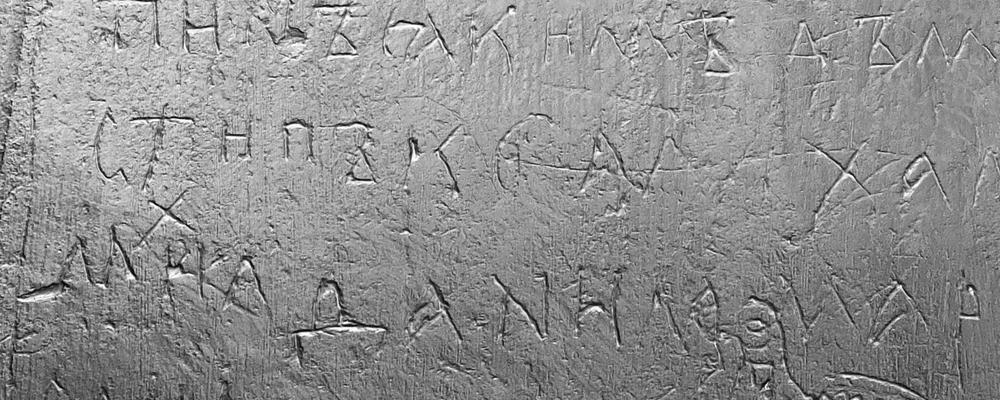

Saint Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv is a thousand-year-old world heritage site according to UNESCO, but it is also a source of knowledge. On the church walls there are more than 7,000 inscriptions in different languages. Together with Ukrainian colleagues, researchers from the University of Gothenburg are now documenting the historical graffiti, which risks being destroyed in the war where Russia is deliberately destroying cultural heritage in Ukraine.

People have always had an urge to leave an impression on the places they visit. Saint Sophia Cathedral in Kyiv is a good proof of that. The church, which was completed in the 11th century, has been visited by wayfarers from near and far ever since, and it shows on the walls in the form of graffiti. Around 7,000 inscriptions have been identified in the cathedral.

“There are inscriptions in many different languages on the church walls. Among other things Church Slavonic, Latin, Armenian and Greek. There are hopes among runic researchers that there may also be Old Norse inscriptions,” says Gunnar Almevik, professor in conservation and leader of a new project that will document and make available the inscriptions in the church.

Russia's war threatens cultural heritage

During Russia aggressive war fare, it has become urgent for Ukraine to try to preserve and document the country's important cultural heritage, which is subject to deliberate and systematic destruction. Researchers in Kyiv therefore contacted the Swedish National Heritage Board for help in documenting the Saint Sophia Cathedral inscriptions. The question went on to the University of Gothenburg, where there is a research infrastructure for digital humanities and expertise in documentation of threatened cultural heritage.

“With modern digital technology, we can create high-resolution images and 3D surface models of the inscriptions as a basis for future research. This source material is then organized into a portal with a user-friendly interface specially built to review inscriptions and make them accessible to both researchers and the public, explains Jonathan Westin,” associate professor in conservation and deputy director of Gothenburg Research Infrastructure in Digital Humanities (GRIDH).

Several techniques are used

Jonathan Westin was together with Gunnar Almevik on site in Kyiv at the beginning of January to do a first basic documentation of the entire interior. Different techniques such as laser, photogrammetry reflectance transformation imaging, a digital raking light, are used to capture the complex informational content of the inscriptions and their spatial context. A working group from Saint Sophia Cathedral was trained to continue the documentation work, which is expected to take a large part of the year.

The inscriptions have attracted previous research interest, but the existing documentation of the source material is transcriptions and does not enable other researchers to make independent interpretations. There are uncertainties partly in how the various cut marks should be interpreted as signs, and partly in how signs should be interpreted as language and meanings.

Valuable research material

“The inscriptions in Saint Sophia Cathedral form a valuable research basis for analyzes of language and writing, of migration, trade, craft traditions, cultural exchange and cultural diversity in Europe over 1,000 years. We know, for example, that the Kievan Rus had strong contacts with the Nordic countries and the foundations of the Cathedral are said to have been laid by the Grand Duke Jaroslav and his wife Ingegärd, who was the daughter of the Swedish king; Olof Skötkonung. Therefore, it would be plausable to find runes among the scribbles in the church,” says Gunnar Almevik.

Until now, research on the inscriptions in the cathedral has mostly been done by Slavic linguists. By making a digital documentation with new technology, researchers with other language skills can look at the inscriptions with different eyes and this can add new knowledge.

Many years of work with the database

The University of Gothenburg has received funding from the research council FORMAS, The Royal Swedish Academy of Letters, History and Antiquities and the Swedish National Heritage Board to carry out the project in collaboration with Saint Sophia Cathedral museum and the National Museum of Ukrainian History, which has a natural continuation at GRIDH at the University of Gothenburg, according to Jonathan Westin.

“The hope is that the source material will be secured during the project period. The work on the database, which involves the identification and interpretation of previously known and newly discovered inscriptions and meanings, will hopefully continue for many years,” says Jonathan Westin.

Contact: Gunnar Almevik, professor in conservation at the University of Gothenburg and project manager, 0766-22 93 01, e-mail: gunnar.almevik@conservation.gu.se

Jonathan Westin, docent in conservation and deputy director of Gothenburg Research Infrastructure in Digital Humanities, e-mail: jonathan.westin@lir.gu.se