Motherhood and Intimate Partner Violence

Short description

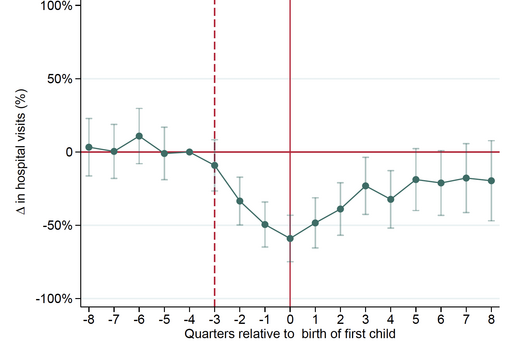

In this project, we ask whether having children is a protective or a risk factor for the incidence and severity of intimate partner violence (IPV). We use Swedish administrative data on childbirth and hospital visits for assault, for the full Swedish population. Comparing mothers to women of the same age but who will have children 4-12 quarters later, we show that hospital visits for assault drop sharply with pregnancy and remain below pre-pregnancy levels for the first two years of the child’s life.

Description

In this project, we ask whether having children is a protective or a risk factor for the incidence and severity of intimate partner violence (IPV). While violence during pregnancy may simply be a continuation of pre-existing IPV, the stress of transitioning into parenthood can trigger or increase IPV. Furthermore, pregnancy may increase women’s emotional and/or economic dependence on their partners, making them more vulnerable within the relationship. From a sociological perspective, motherhood is often used as a tool of control and manipulation by the abuser where the partner may exert control over the mother by threatening to harm or take away the children. At the same time, a woman may be trapped in an abusive relationship as she may be reluctant of leaving because she fears losing custody of their children or not being able to financially support them. Even when women leave the relationship, custody discussions and exchanging children may be an increasingly important factor in postseparation violence. From evolutionary theory, motherhood also plays a prominent role in IPV because men may use physical and emotional abuse to control their partners and ensure access to their offspring. Last but not least, an increase in partners’ time together as the mother is now more present at home, nurturing the child, creates more opportunity for abuse.

In contrast, IPV may decrease with motherhood as women become more valuable within the relationship as they bear and nurture the child. Alternatively, violence against mothers may also decrease as maternal leave and potential subsequent withdraws from the labor force lower women’s economic independence (male backlash theory), and/or exposure to other men (evolutionary theory), reducing their partners’ stress and anxiety. Motherhood may also lead to a reduction in IPV if the arrival of the child decreases women’s willingness to accept being victimized and gives her the strength to leave an abusive relationship. At the same time, as parenthood may increase both partners responsibilities towards their child, they may engage less in destructive behaviors and, hence curve engagement in substance abuse, which is directly related with violence. Finally, antenatal, perinatal, and toddler care offers an opportunity for identifying women experiencing violence during pregnancy, post-partum, and the first years of the child as frequent visits to health-care providers offer an ideal setting for identifying and addressing issues of abuse.

Understanding whether IPV increases or decreases with motherhood as well as the reasons driving this change is a top priority and is crucial for designing public health policies that eradicate domestic violence. For example, if we find that it is the stress of transitioning into parenthood that triggers or increases IPV, policy makers ought to offer more resources and emotional support with prenatal care. If instead, the increase of IPV is driven by men’s need to control and manipulate their partner when the child arrives, efforts ought to be directed at challenging societies’ hegemonic masculine norms through public health awareness campaigns and propelling alternative forms of masculinity by incorporating them in teaching them as early as primary education. Similar policies should be implemented if IPV decreases with motherhood because of a reduction of men’s stress and anxiety as their partner is complying with traditional gender norms by becoming a home maker and primary caregiver of their child. Alternatively, if the decrease in IPV is driven by women’s higher and more frequent access to health-care providers, the policy implication would be to offer such type of services more frequently and broadly to all women (or to air public health awareness campaigns underscoring the risk of victimization and perpetration with substance abuse consumption). A decrease in IPV driven by fathers’ curbing of alcohol abuse would trump the need for public-health policies aiming at alerting on the family costs of substance abuse.

This project use a population-wide longitudinal dataset, covering the medical history of the entire population of Sweden between 2001 and 2016, to analyse the dynamic effects two years before and after the birth of a child on domestic violence. We use three alternative measures of IPV victimization: (1) hospital visits for injuries caused by assault at home or an unspecified place, our broader measure, (2) hospital visits for injuries caused specifically by IPV; and (3) over-night stays for injuries caused by assault, which captures the most severe cases. To address potential concerns with selective care-seeking and misreporting at the hospital, we plan to conduct a battery of sensitivity test taking advantage of detailed information on different types of, and reasons for, hospital visits. In addition to medical records, we also have both partners’ employment and earning records, highest achieved degree, medical records on substance abuse and mental health, and couples’ marriage, divorce, cohabitation and separation.

To address the selection issues related to the fact that mothers and childless women may differ in preferences, risk taking, and lifestyles, we estimate a stacked difference-in-differences model with quarterly data based on mothers’ age-at-birth comparing mothers to women who have their first child within the next eight quarters. We control for individual fixed effects, ultimately comparing women’s victimization risk after the birth of her child to her own risk right before, relative to changes observed in the comparison group (women who have their child at an older age). The model also controls for individuals’ change in yearly income, marriage status, and part-time or full-time employment.

The result of our initial analysis suggests that hospital visits for assault drops sharply at the onset of pregnancy, and slowly increase after the birth of the first child. After two years the gap between mothers and mothers-to-be is still large and statistically significant, indicating that the drop in hospital visits for assault is persistent for several years after birth.

To the best of our knowledge, this will be the first study to analyse the dynamics of victimization around motherhood using the entire population of a country. In addition, the study aims to identify the mechanisms driving our findings, providing evidence-based research useful to guide timely policy making.

Participants

Sanna Bergvall (University of Gothenburg) and Nuria Rodriguez-Planas (City University of New York (CUNY), Queens College; Institut d'Economia de Barcelona (IEB), Universitat de Barcelona.