- Home

- Research

- Find research

- Embodying and documenting site-specific performance art

Embodying and documenting site-specific performance art

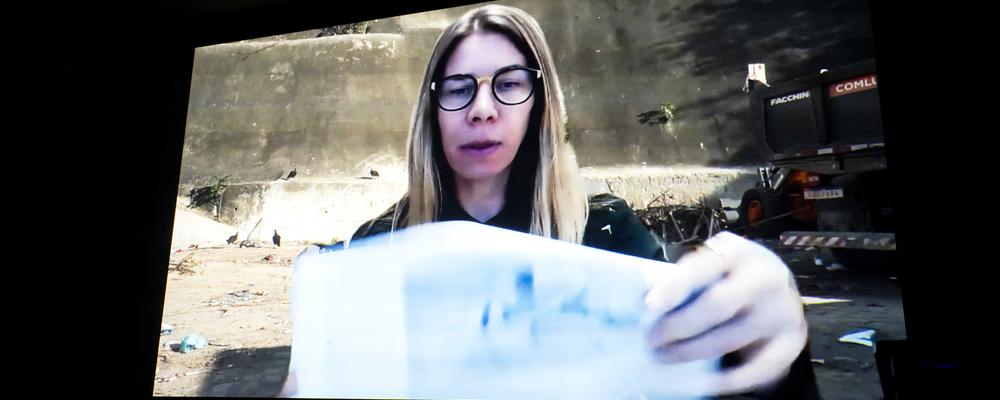

The body and the senses play an important role in Nathalie S. Fari's site-specific performance art. In her doctoral thesis, she investigates and maps public spaces in Gothenburg and Rio de Janeiro in a series of laboratory sessions. The labs are documented and turned into performance art in video format.

Nathalie S. Fari obtained her doctorate in Performance Practices at the Academy of Music and Drama in May 2024, after defending her thesis "Situated Agencies: Mediating Places Through the Body". The project examined how site-specific performance practice can be addressed through an embodied and documentary approach.

Drawing from place-based research, performance documentation and posthumanism, Nathalie S. Fari carried out a series of performance laboratories in collaboration with artist researchers at Götaplatsen in Gothenburg and ”Praça Mauá” in Rio de Janeiro. A central purpose of these laboratories was to explore the relationship between embodiment and audiovisuality, especially by experimenting with how the audiovisual traces of a laboratory work can serve both as data and a creative source for developing screen performance as research. This conversation focuses primarily on the part of the project that was carried out in Gothenburg.

What was the starting point of this project? And what is it really about?

Well my project is really about working site-specifically and engaging with places. When I moved to Gothenburg I needed to find a place that I felt had the kind of different layers that I like to look at. For example that there is a public life, and not just empty beautiful architecture. And that it has some historical meaning and then also that you as a performer feel that you can be in that place and do your work. So, that's my starting point and then I develop performance material for that specific place, which in turn is mediated. In this case it was mediated for a camera, so it's not a live performance per se.

And why did you choose Götaplatsen for this project?

So, I was coming from Berlin where you have a lot of public life and discussions about public space but when I moved here to Gothenburg I felt at first that there's not so much of that. So that's why I ended up at Götaplatsen, which for many locals is probably not the place to hang out, but at least I could see all those layers of a very diverse public life, not just due to the cultural institutions there but also due to the all the events that take place at Götaplatsen. And you have this monumental architecture which has a historical significance. But when I started I had no idea of where I would end up, how I would develop a performative engagement with the place. But that's actually what it's all about.

The title of your thesis is “Situated Agencies – Mediating Places Through the Body”. Would you mind explaining on an atomic level the meaning of that?

Okay, so situated agencies is… we as humans have agency, meaning we have a possibility of being present and engaging with not just other human beings but also everything that is in a place. And the situatedness is that you really are physically and mentally present, but also you are embedded in a specific environment for a specific time. So in these cases the situatedness is also always being in relation. So it's a form of creating relationships with the people around you, with animals and objects, with atmosphere… with everything that is surrounding you at a specific place. What kind of structure, what does it do to me when I am there? How do I perceive the space, the birds, the animals also have agency… you have a lot of the human agency, people that are there for a reason.

What you are describing sounds not so different from maybe what urban developers or architects might investigate: For instance, if you want to build a city square you have to think about where do people go, what kind of errands do they have. Do you know what I mean?

Well, a huge difference is that urban planners and architects create spaces for functionality, so they are looking at how people will use the space. That's not what I'm working with, for me the place is a creative source and not just about the functionality. It is much more about how I can be affected and affect the place. And in my case my engagement with a place is through the body and it's through performative strategies. So it's not that I'm thinking people should walk from left to right and now I will build the corridor so that they can cross easier. For sure it's important to understand how places are used, but I'm interested in how the place can be a creative source for a performance work.

So, the performance is created in dialogue with the physical and historical meaning of the space. And also with other aspects?

Yes, there’s also the social meaning, the public life, but then also one aspect which I like to call hidden narratives of a place. I want to look for the narratives which haven't been told. Sometimes it's a very simple thing, so for example in the case of my short film “I am the Camera”, which is a performative engagement with the Hasselblad Memorial at Götaplatsen. The statue holds a camera because it represents the technology of photography. I use the camera as an imagination that it is portraying Götaplatsen 24 hours a day, that it is a hidden camera because of where it is positioned. It's not what people usually associate with Götaplatsen and they wouldn't go there because of that statue. There are the big obvious attractions like the Poseidon fountain and the monumental stairs to the museum, but I wanted to avoid all those. This is what I call a hidden narrative. It triggered an imagination from where I could start to develop something.

Let's stay on the topic of the camera for a moment. The location of the Victor Hasselblad statue might just be a coincidence, but I think it says something about the meaning of the camera and the photographer. Nobody sees it but it's looking out on this significant place, and this relates to the act of putting a camera in front of one’s face. It's like you hide from the situation. And similarly I get the sense that your work is about the dialogue between the person and the space, but then the documentation is sort of an additional layer between you and the audience?

I felt that the camera can frame and can give me so many details. The camera creates a double perspective where you can create a sort of distance but also be quite close.

But also, the use of cameras in my work has been with me before starting the project so it was always present and then here I had more technical possibilities of using them and putting more and more emphasis also on the moving image.

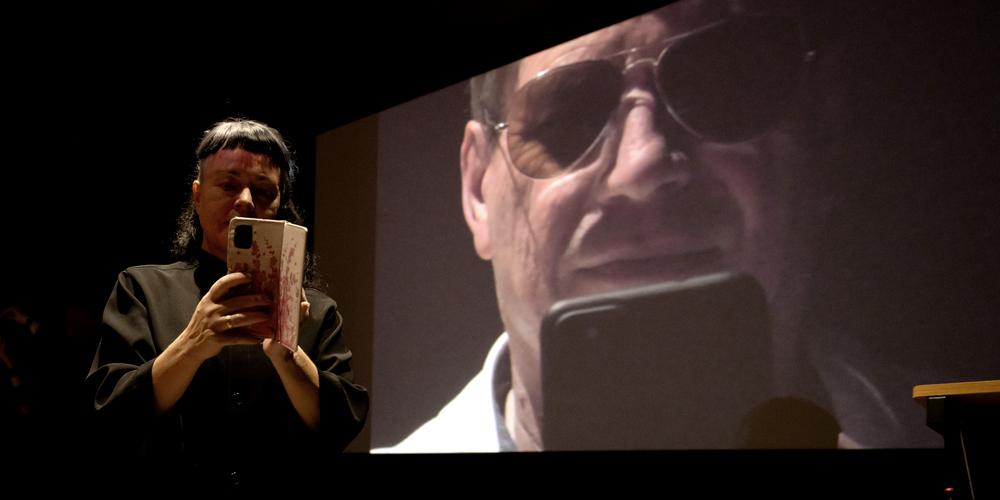

And also important is that you create a material which is on site but when it comes to creating the film you are in an editing programme. This became for me a kind of “reperforming the space” and that's what became so interesting. That documentation is not just documenting what is happening, which is necessary anyway for many artists, if they want to apply for festivals and so on. They always need documentation to be able to sell their work, so this has always been an important aspect for me, but I consider documentation also as an artistic practice, how to document and how to generate an interesting material so that you have more options, and that you might be able to create an artistic piece with the material. And this site specific engagement allowed me to generate this material and the editing was a possibility of re-performing the space and then creating a narrative. For example “I am the Camera” with me interviewing the Hasselblad camera, that would have been almost impossible to do as a live performance. Because we had very restricted access to this camera. Hasselblad Center said yes to my proposal, and they liked the idea and then they made the camera available for us. It’s a camera that has landed on the moon and it's a historically very significant piece that they keep in a safe. So by filming instead of doing a live performance, this was possible to do.

When you say documentation, one might get the impression that it's basically about the camera being a passive observer and you're just trying to capture what is happening. But, I think looking at the videos in your labs there's more to it. And also in this funny way it's like when you're interviewing the Hasselblad camera you're giving the camera agency, you’re turning it into a being so I feel like that's sort of symbolically doing the same thing as what’s happening in the performances. So, for instance sometimes you use a GoPro camera and it's more like the camera is an active part of the performance.

Yes, the camera has a performative, I like to say narrative agency. It is a co-participant in the performance labs. So, not just in the conventional terms of documentation, where you place a camera on a tripod and push the button to record a performance.

Here, I am also thinking about where to place it, placing different cameras and working more like in a cinematographic process. The point is also to create a rich material that I can use in many ways in the editing or in the narrative thinking. But still, my entry point is totally different from that of a filmmaker.

Your starting point into the project seems to be not so much from the point of view of documentation and cameras? It sounds to me like this came into the project partly through coincidence because of the pandemic?

When I entered the project, I had three different areas that I was looking at in the laboratories: One is documentation. Another one is physical training, how you prepare the body for such a practice when you're working in a public space, which is very different than for actors on a stage. And then the third one was about methods of exploring how one deals with places. And then by chance I found the Hasselblad Memorial where the camera is absolutely key, so I think this led to the camera suddenly becoming so prominent in my project.

But in a site specific project you start from a place and you never know where you're going to end up! But that's the beauty of it. It's different than on the stage where you come with a play with an idea you do two months of rehearsal. With site specific projects you often don't know and there’s a lot of risk. But in this case I'm very grateful that Hasselblad came into the picture, it was a fruitful coincidence.

I'm thinking that our relationship to cameras has changed so much over the last 20 years. As a performing artist you must have experienced this change, how nowadays the audience is often hiding behind their phones? Is this a part of what you are examining, how interactions today are affected by the fact that they are more mediated through technology?

Yeah for me this issue is interesting enough that I would like to continue, and I have previously done one project that examined how we navigate through spaces with mobile phones. In Sweden the digitalization is very advanced and people are spending… well, for me it's way too much time, in front of the phone.

But anyway, I think everyone is documenting their lives full time. That's why one of the characters in the short film I am the Camera is an influencer. Because the influencer is the one that lives for the camera and makes money with the camera. But my way of approaching it is more in the form of satire. I just see it as so absurd, and I love to observe how people are behaving and maybe my role as a performance artist and as a filmmaker is this observatory mode.

It's a huge change especially in the past 10 years and we still don't know where it's going. Probably in some years people will be walking with Google glasses. I see it also from a critical point of view and that's why I bring the attention to a camera that landed on the moon. It is for me a way of rethinking our relation with cameras because this one had a really super important mission, documenting and showing something that no-one had seen before.

Are we going too deep into the whole camera aspect of your project?

No, but we can also look at another important part of the project, which is a more sensorial approach to places. From this point of view the camera is just an interface, but the entry point is through perception, through the senses. And, to get back to the title, hence mediating places. You’re bringing your senses, your skin, your hearing, your touch, your gaze… I like to use as a metaphor that the body in a public space is a kind of a seismograph detecting the performative qualities of the place.

And this is a very important entry point because you need to be there as a body and sense the place and see what you can take out of it. A lot through improvisation.

Through the years I developed what I call body mapping labs. I have been giving them in different contexts, also to architects at Chalmers, using those three main methods: mapping, sensing and documenting a place. Besides all my artistic work I'm also a yoga teacher and I come from dance, so I have been working with the body for many years.

I try to give lab participants the possibility of engaging and then that's the main method for generating a material, in whichever medium that the participants choose.

Even though it makes sense to use our human senses to try and figure out how to make for instance a public space that feels good for humans, it is still problematic because it’s not something you can measure, it’s based on emotions and subjective experience. Do you think that outside of the arts these kind of methods might be frowned upon?

Well, it is indeed based a lot on subjectivity. But still, when I did the body mapping at Chalmers the architecture students thought it was very helpful to understand the relationship between the human body and the space, because they often create spaces mentally but they have no idea how those spaces might affect people. By taking in account the embodied aspects you can make places pleasurable which could change our way of interacting a lot.

One would think that when spaces are designed for humans, a human perspective would be more integrated?

Yes. I grew up in Sao Paulo with those skyscrapers, and there's so many places where you just feel so oppressed because you don't have space to breathe. There is no urban planning. I mean the city just grew like an explosion and this affects the people, it affects the traffic and the air… it affects so many things. I think we tend to forget how important it is to activate a form of bodily engagement.

Nathalie S. Fari obtained her doctorate in Performance Practices at the Academy of Music and Drama in May 2024, after defending her thesis "Situated Agencies: Mediating Places Through the Body". Click on the title to access of the thesis and related videos .