Reyhaneh invites the exhibition visitor to participation

When Reyhaneh Mirjahani entered HDK-Valand’s Master of Fine Art programme, she had only a vague idea of where she was headed. It became a two-year period of critical thinking – not least questioning the role of the artist. She has now settled into an art career in which these questions continue to take centre stage.

Reyhaneh Mirjahani has been doing a lot of travelling lately. Among other things, she has contributed to the educational platform of the Riga Biennial in Latvia and the Nida Art Colony in Lithuania. She also has a project under way in the Netherlands.

Sometimes she works from home in her flat in Gothenburg, but not often. Her work as an artist is hard to do remotely. She usually collaborates with partners, and this almost always requires that both she and her audience are there in person when one of her works is presented. As an example, she mentions the on-going art project An Experiment on Agency. She launched the project back in 2019, when she was still at HDK-Valand, but had to put it on hold during the pandemic. It wasn’t until this year that she could perform it – at the Skogen (the Forest) cultural stage in Gothenburg.

In this work, Mirjahani explores how participatory installations can raise questions about the possibilities we have to influence the contemporary socio-political context. The point of departure is a series of ethical dilemmas in which none of the alternatives is particularly desirable, resulting in a lose-lose situation. It’s a theme that takes on an extra dimension when Mirjahani talks about growing up in Iran. Her experience of living in a dictatorship, living in Eastern Europe and later coming to Scandinavia has affected her art and the issues she chooses to work with.

“In general, I’ve lived through situations in which I’ve been forced to choose sides,” she says.

“That’s never been easy, and I’ve never gotten it a hundred per cent right. That complexity is something I carry with me all the time.”

She earned her bachelor’s degree in sculpture at the School of Fine Arts in Tehran. That was followed by several years in southern Poland. It was there, while doing a residency in Kielce, that for the first time she experimented with allowing exhibition visitors to participate in a work of art – a ceramic art installation.

“It was a hit!” says Mirjahani. “And although I had no finished idea, I realised that this was the path I wanted to take and also that I wanted to keep studying.”

To questioning the role of the artist

Since the educational programmes offered in Poland were not what she was looking for, she chose to apply for a place somewhere in Scandinavia. One of the schools that interested her was HDK-Valand. “The focus here was on the socio-political context and the role of the artist,” she says. “Not on the form, but on what you want to convey. Also, we were encouraged to collaborate.”

Mirjahani describes these years at HDK-Valand as a roller coaster ride. It was a chance to work on herself and with issues related to art and the role of the artist in society. “It was a constant struggle with questions about who, how, and why, and I’m glad now that I put myself through that,” says Mirjahani. “That led to my way of looking at art as a method and as a language for discussing the topics I want to raise.” Art as object plays a very minor role in her work. She got started on this path by making sculptures, but today she sees sculpture more as just one possible tool for achieving what she wants.

Since graduating from the master’s programme in 2020, her work has increasingly developed toward the conceptual, and she even went through the CuratorLab programme at Konstfack, the University of Arts, Crafts and Design in Stockholm.

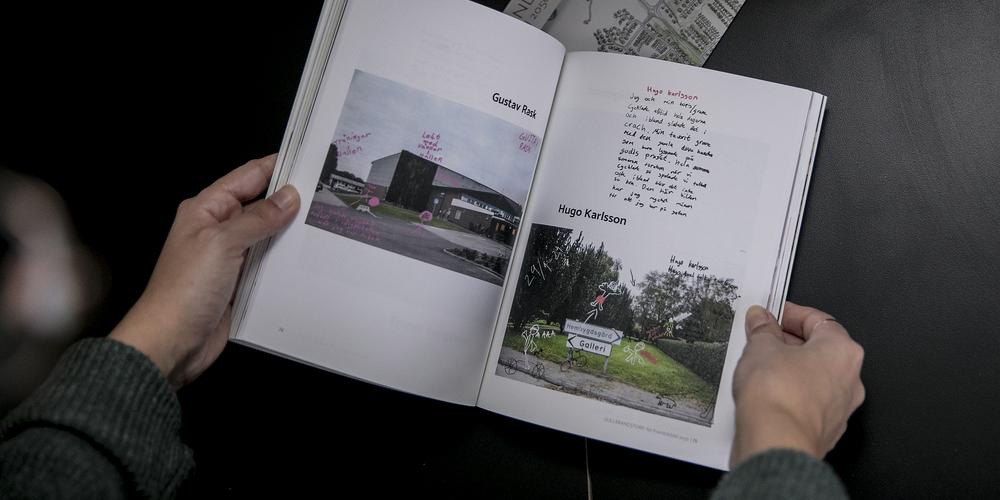

To illustrate how she works, she shows us several exhibition brochures and a book entitled Gullbrandstorp: för Framtidsbild 2050 (Gullbrandstorp: For the Future Image of 2050). It includes images and stories from residents of the little Halland village of Gullbrandstorp and is the physical result of a public art project she has just completed.

“It was actually a land art project, but I didn’t want to just pop up in the community, create something on the site and then disappear,” says Mirjahani. “Instead, the inhabitants of Gullbrandstorp got a chance to share their experiences of living in the area, and I developed a way to archive their stories for the future.”

What does your own view of the future look like? What are you going to be doing in ten years?

“I take one small step at a time and see where it leads me. But I’d be happy to keep doing what I’m doing today – with art projects both in Sweden and abroad.”

Text by: Camilla Adolfsson